It is not normal protocol for World Bank vice presidents to make presentations. But this was a special occasion: it was March 2005 and Pakistan’s new-found prosperity was at risk. So as General Musharraf sat to listen at the Presidency in Islamabad, Praful Patel, vice president of South Asia for the World Bank, and not one of his juniors, delivered the news: unless proactive policies were adopted, Pakistan would face a major energy crisis in three to four years.

As a former World Bank vice president, Shahid Javed Burki was also there for the presentation. He remembers that day clearly. “At the time, there was talk of an energy surplus. But really, there was none.” GDP was increasing rapidly and the country’s appetite for energy was eating into whatever excess production capacity was there.

The presentation had an impact on Musharraf. Afterwards he invited Burki, who had served as Pakistan’s finance minister from 1996 to 1997, back to his office. “Do you know this man Patel?” the general asked Burki of the Ugandan of Indian descent.

“Very well. He was junior to me at the World Bank. In fact, he showed me his recommendations before he presented them to you.”

“Should we take his conclusions seriously?” Then, right there, upon hearing Burki’s “yes,” the then president and general called Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz on the phone. The general gave the order: get moving on this.

* * *

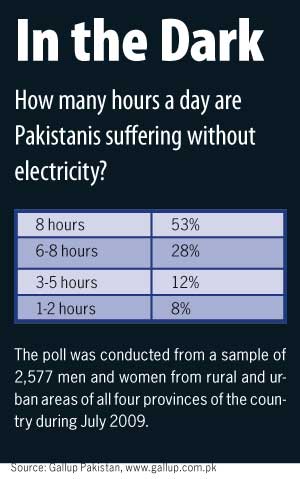

Few positive moves have been made since then. The proof is in the magnitude of the current crisis. Electricity shortages nationwide hover around 3,500MW. As a result, loadshedding is a daily occurrence. Business and industry has been stifled across the country. And as always, ordinary Pakistanis suffer the most. According to a Gilani poll conducted by Gallup Pakistan in July, 83% of Pakistanis say they have been affected by loadshedding, while a staggering 53% of the nation claims to live without electricity for more than eight hours a day.

Power shortages are just one part of the overall problem – money is another. The rising price of oil in the global markets was a factor in pushing Pakistan to the edge of bankruptcy in 2008. Oil imports alone have cost Pakistan almost $21 billion in the last two years. In the process, Pakistan’s scarce foreign reserves plunged from over $16 billion in 2007 to a low of $6.7 billion in October 2008. Islamabad went running to the IMF for a multi-billion-dollar bailout and turned to the newly created Friends of Pakistan with another begging bowl in hand.

The financial woes of the government have crept into the energy sector too. The entire industry is saddled with debt, as most players struggle to pay their bills because they can’t collect on their own receivables.

The economic costs are being felt across the country. Last year GDP growth was a paltry 2%, exports missed budget targets by 19.5% and inflation was 20%, far off the government’s budget goal of 12%. Jobs, poverty reduction efforts, social programmes and quality of life are all on the decline.

The energy crisis has metastasised across the nation. And it is, without a doubt, the worst energy crisis Pakistan has ever seen.

With Pakistan’s 62nd birthday around the corner, the government is scrambling to find fixes. Like an intravenous drip, it is slowly trying to inject new power into the national system, megawatt by megawatt, just to keep the economy alive – and denizens calm. Islamabad has promised that 600MW of electricity would be added in August. Late last month, the Federal Minister for Water and Power, Raja Pervez Ashraf, announced that rental power plants would be operational by the end of the year. These in combination with a group of new Independent Power Producers (IPPs) will, said the honourable minister, help end loadshedding by the end of the year. Lower winter demand for electricity will undoubtedly help in potentially reaching this promise too. But guaranteeing a quick, permanent end to power outages is an impossibility in the current crisis. As soon as summer rolls around again, demand will, once again, skyrocket. In summer months, a one-degree-Celsius increase in temperature can raise electricity demands by 40MW on KESC alone, says its chief operating officer. Of course, loadshedding may also be lower by next year as businesses and industries continue to slow down or shutter up, reducing overall industrial and commercial demand in the country – in 2008-09, large-scale manufacturing declined by a bone-crunching 7.7%.

Besides promising to end the country’s miseries, Minister Raja Pervez Ashraf has also been reminding voters of who to blame: not him. He insists that the past regime should have built the electricity-producing infrastructure. They didn’t. And now we are suffering.

The honourable minister is not altogether incorrect. The “past regime” did have time to act. Not only did Pervez Musharraf and Shaukat Aziz receive thoughtful warnings, but also, undoubtedly, they were reminded of a cautionary tale. Pakistan had, not so long ago, stumbled through an energy crisis in the late 1980s and 1990s. A decade of strong economic growth under the military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq produced huge annual jumps in energy demand. But energy supplies, especially electricity generation, lagged behind. The supply-demand gap put the brakes on the prolonged boom. Industry faltered, and consumers faced long days and nights under regular blackouts.

The fact is, though, that the past regime did do something. “Approval for 10 new IPPs (most scheduled to start generating power before the end of 2009) was given in the Musharraf-era,” says former PPP Senator Enver Baig. The capacity for these 10 would be just over 2,000MW. “Yet the PPP administration is taking credit for this.”

The fact is, though, that the past regime did do something. “Approval for 10 new IPPs (most scheduled to start generating power before the end of 2009) was given in the Musharraf-era,” says former PPP Senator Enver Baig. The capacity for these 10 would be just over 2,000MW. “Yet the PPP administration is taking credit for this.”

The rental units, though, are this PPP government’s remedy. Unfortunately, all of the rental units will run on oil. The problem is the government really has little choice at this time. As expensive as rental plants are the alternative is worse. “Rental plants are a legitimate response,” says 26-year World Bank veteran Burki. The short-term costs may be high, he says, but rental plants are the right response in the face of huge industrial and GDP losses.

Not everyone agrees. Political analyst Imtiaz Gul questions this. “It’s a quick solution, but if they have money for up-front payments now, why don’t they pay half that to the IPPs for increased power – because the IPPs have the capacity.”

IPPs across the country are struggling. They are providing electricity but are not getting paid for it by the federal government. As such, many are struggling to pay their own bills. They have drastically cut back on power generation to cut fuel costs. The fact is the whole energy sector is struggling with debt and cash-flow problems. Everyone in the sector owes somebody else, and nobody seems to be able to pay first. The common link in most of the circular debt chains constraining the sector is the federal government, which pays out massive subsidies to power producers so that tariffs are kept artificially low for consumers. This “circular debt” crisis is a noose that is quickly tightening around the neck of the entire nation.

On July 29, the National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Finance heard the latest estimates of the tangled web of circular debt. According to a report in the Daily Times, Salman Siddique, secretary finance, explained to the committee that circular debt had been reduced to Rs 170 billion, though receivables under circular debt sat at Rs 456 billion. The Pakistan Electric Power Company (PEPCO) itself has debts worth billions of rupees.

Baig says that the PPP inherited this circular debt problem. Where the current government has failed, though, is in not making enough provisions in the budget to close off the debts to the IPPs. The budget does, however, allocate Rs 646 billion for the Public Sector Development Program (PSDP). And it is from here, believes Baig, that the government should take the money it needs. “Fifty percent of that money will be lost to corruption anyway,” he says. Once the government reallocates money from the PSDP to the IPPs, loadshedding will be curtailed, and the textile industry can get moving again and re-hire its workers. “The jobless rate will go down and lawlessness will decrease. If a man cannot feed his children, what will he do? He’ll become a dacoit.”

Given that the electricity sector and oil sector are linked, the oil industry is in dire straits too. Pakistan State Oil (PSO), a leader in Pakistan’s energy sector, is saddled with monstrous debts of its own. According to its financial statements, as of March 31, the company had trade debts of Rs 81 billion, with trade receivables of almost Rs 34 billion. Throughout 2009 the supply of oil has been severely under pressure as many refineries have curtailed the flow of oil to PSO because of its financial woes. Larger shortages of oil would take the overall situation from bad to worse.

The finance ministry is working its way through the debt, but for many it seems too slow. “The government has been unable to convince lenders of their sincerity to find a solution to this circular debt issue,” says writer and analyst Imtiaz Gul, before dropping a huge accusation. “Some of these IPPs are systematically being pushed into bankruptcy. There are people with connections to the government that want to take over their plants,” he suggests. He doesn’t name names, and instead decides to wrap things up. “If we can resolve the circular debt issue, the IPPs can return to about 80% capacity and that will take care of most of the loadshedding.”

The federal government is looking for the next installment of its recently increased $11 billion IMF loan to help work through the debt portion of the energy crisis. But it is believed that the IMF is looking for the government to make some changes: specifically raising electricity tariffs. Islamabad complied once, but the Supreme Court overturned the rate hike. Now, Islamabad, reeling from a summer of nationwide protests from angry voters, is averse to doing anything that would irk frustrated citizens any further.

Addressing circular debt and ensuring that the rental plants get up and running are immediate challenges – and both will affect the supply of oil. Fixing the pricing models for end-user energy in Pakistan is critical, too, and probably will take more time, but definitely needs to be addressed sooner than later. Many experts believe that any attempt to fix the pricing system must look at adjusting tariffs to reflect fluctuations in primary energy costs, while providing assistance to the poorest segments of society to ensure accessibility. Furthermore, economic incentives need to be implemented to promote conservation at home and efficiency at the industrial level.

* * *

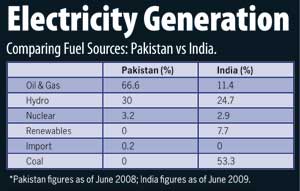

None of those issues will disappear forever without tackling the country’s energy mix. Oil and gas make up 78% of Pakistan’s primary energy supplies – this includes fuel for the transport sector. Sixty-seven per cent of electricity is generated by oil and gas. This has to be changed.

To do that, the country needs a long-term energy policy. But there’s the rub. “There are no long-term plans,” says Burki. “State policy is made in response to crises instead of strategic planning.” As a result, Pakistan’s dependence on those two combustible fuels is only growing. All the new IPPs scheduled for 2009, 2010 and 2011 will generate power based on either oil or gas. Look at what’s happening, says Burki. “The high cost of imported fuel causes pricing problems. And every time Islamabad solves a crisis, it increases the dependence on foreign oil.” This compounds the country’s financial woes and hampers GDP. And Pakistan already has one of the highest percentages of furnace oil-generated electricity in the world.

All that makes sense when talking about oil. But to many, though, natural gas doesn’t seem like such a bad energy source to be dependent on. It is cleaner and much cheaper than oil, and Pakistan has lots of it. The problem is Pakistan has become the largest consumer of compressed natural gas (CNG) in the world – and its domestic reserves are expected to start depleting in 2011. Across the country, people have started moving heavily towards gas in every part of their life: cars, stoves and home generators. Reversing that dependence is not an easy thing to do. As a result Pakistan will also become a big importer of natural gas.

This is troubling from two perspectives. Firstly, there is the all-too-familiar drain-on-foreign-reserves angle. Secondly, there is the issue of suppliers. Michael Kugelman, co-editor of the book Powering Pakistan: Meeting Pakistan’s Energy Needs in the 21st Century, says, “Given that most of Pakistan’s rapidly growing oil and gas imports presently come from volatile, unstable global regions, there is also a strong geopolitical argument for transforming Pakistan’s energy mix into one that emphasises a local resource base.”

Focusing on developing and using a local resource base will allow Pakistan to steer towards what should be its two main goals: sustainability and energy security. Pakistan doesn’t have to look far to see a model fuel mix for electricity generation. In India, the government has developed an energy mix based on low-cost, abundant local resources. And even though the balance of the internal structure of the mix may shift towards more oil and gas as India ensures it has enough energy to power its strong economic growth story, the long-term outlook and focus necessary to create its present mix of 53% coal, 25% hydroelectricity and 7.7% renewables is something to emulate.

Right now, an energy mix for electricity where 78% comes from coal and hydroelectricity, instead of 67% from oil and gas, is simply a pipe dream. But moving in the right direction can be done. Pakistan must implement a policy based on water and coal, says Burki. “This is Pakistan’s only long-term policy.”

There is no sign that this is seriously being pursued, though. Yes, there are new coal projects planned by both IPPs and the KESC, while there are also new dam projects in the works by WAPDA, but there is little to show that a formal commitment has been made to pursue this path aggressively, especially with the huge number of furnace oil-fuelled plants to be fired up over the next three years. Besides, plans need to be made now, investors need to be brought in and development of the raw resources, like coal, need to be accelerated. A shift like this entails major coordination by many government ministries and agencies.

There is no sign that this is seriously being pursued, though. Yes, there are new coal projects planned by both IPPs and the KESC, while there are also new dam projects in the works by WAPDA, but there is little to show that a formal commitment has been made to pursue this path aggressively, especially with the huge number of furnace oil-fuelled plants to be fired up over the next three years. Besides, plans need to be made now, investors need to be brought in and development of the raw resources, like coal, need to be accelerated. A shift like this entails major coordination by many government ministries and agencies.

Despite coal’s dirty image, the use of it in Pakistan is being supported by many experts for two reasons: it’s abundant and it’s cheap. Pakistan’s coal reserves are the sixth largest in the world and the cost of using coal for power generation is about half that of furnace oil. The 185 tonnes of coal reserves in Thar may be low-grade lignite coal, but it still can be used for electricity generation. In Greece, lignite represents 81% of that country’s primary energy production. Naveed Ismail, CEO of KESC, says, “In coal plants, the boilers are designed specifically for that type of coal. So coal from Thar is perfectly good coal, we just have to design a boiler for it.” Besides, says Ismail, “Currently, imported coal is cheaper than subsidised gas.” And carbon capture and storage technology removes the fear of excessive emissions. “All ash is captured, all CO2 is captured and all sulphur is captured to make gypsum. Environmental concerns are not an issue.”

Maria Kuusisto, an energy and mining analyst with the Eurasia Group, warns that the development of the Thar coal reserves requires long-term bureaucratic and technical commitment. “Even coal needs a huge investment,” she says. “In fact, top-notch technology is needed to process Thar coal. This hikes up the price. A lot of money is needed for infrastructure because mining it is a complex process. You also need to build high-tech plants, and you need to do all this before generating power or money.” Kuusisto cites the example of a Chinese group who were interested in developing and using Thar’s lignite coal. “They were interested, but they left the project. They failed to come to an agreement on tariffs for power generation.”

* * *

The 1970s changed the face of power generation in this country. After a decade of outstanding growth in the 1960s, energy surpluses started to dwindle. Looking ahead, though, the government of the day understood that major, long-term initiatives were desperately needed if Pakistan was to return to a path of strong growth. Those initiatives led to the construction of the Mangla and Tarbela dams. “For a number of years, the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) was a model public sector institution in the developing world for undertaking development works,” writes Burki in an essay in Powering Pakistan. WAPDA not only presided over the construction of these massive projects but it managed their growth: over the years generation capacity grew from 636MW to 7,000MW. This is a Pakistan-energy success story.

The Kalabagh dam should have been another. Speaking over the phone from Singapore, Burki doesn’t hesitate to drive home how necessary the Kalabagh dam project is for Pakistan’s energy security. “Vital. Critical. We’ve known this for 20 years. The United Nations Development Programme had published a report in the early 1980s. It was very elaborate, very professional. And it stated the necessity of Kalabagh.”

Pervez Musharraf agreed. When the general took over the presidency in 2001, he pushed for Kalabagh, says Burki. But as the project became more and more controversial, with opposition from different provinces over a range of issues and fears, he started to waiver. “Over time he became very sensitive to criticism. His decisions became politicised. And soon, he was not prepared to pursue Kalabagh.”

Today, WAPDA has major projects in the pipeline. One is the Diamer Bhasha Dam. With 6.4 million-acre-feet of capacity for water storage, this mega project will benefit local agriculture and generate 4,500MW of electricity.

Not everyone is thrilled about large hydroelectricity (hydel) projects. “The useful life of a dam such as Tarbela is about 100 years, for which approximately 100,000 people were displaced, not to mention the inundation of 23,000 hectares of arable land,” writes Saleem H. Ali in his essay contribution to the book Powering Pakistan. “Even the increase in cultivable land requires further ecological study in cost-benefit analyses, since in many cases mismanagement of the irrigation schemes led to salinity and water-logging, and an eventual loss of arable capacity in 22% of the Indus Basin.”

Ali also writes that the 2005 Kashmir earthquake should jolt planners in Pakistan into being concerned about the vulnerability of dams to seismic activity. They need to look no further than China for an example of a catastrophic dam failure, he writes. In 1975, a typhoon dumped a year’s worth of rain (1,060mm) in one day, causing the rising levels of rainwater to breach the Banqiao Reservoir Dam. Massive flooding killed at least 26,000 people, with the death toll rising by another 145,000 in the following weeks. Over 10 million people were displaced.

His list of risks for large hydel projects doesn’t end there. The belief that large dams are “emission free” is also losing support, he writes. “There is potential for methane generation from dam reservoirs.” As methane is a greenhouse gas, dams larger than 10MW are losing favour internationally.

This doesn’t mean hydel should be ruled out of the energy mix. It simply means think small. Smaller hydel projects are more flexible to engineering redesign and can be constructed along some of Pakistan’s smaller rivers, such as the Kunhar, Swat and Chitral, writes Ali.

Maria Kuusisto agrees. “Hydro is renewable, clean and abundant. But small hydro is preferred,” she says. “Mini projects can provide significant supplies, especially in local areas. They are less politicised and easier to implement.” Pakistan, with the help of the Alternative Energy Development Board (AEDB), has already set up 253MW of micro- to small-sized hydel plants, producing less than 50MW each.

There are plenty of things the government can and has been doing to help diversify the energy mix further. The AEDB has been busy trying to advance renewable energy sources and technologies in Pakistan. However, alternative energy will be no panacea to our energy shortages: it will probably only cover about 2% of the energy demand by 2025. The country is also moving ahead with more domestic oil and gas production, auctioning off blocks for exploration in late August. Nuclear energy is a more controversial area given Pakistan’s internal strife, but there are still opportunities (though none to help in this present crisis).

Shifting the country’s overall energy mix significantly may sound impossible. In 2005, the Planning Commission projected that the percentage share of the total energy pie for different energy sources would shift only slightly by 2025. Specifically, the shares for oil and gas in the overall mix would each drop by 4% over 20 years, with small increases for coal, hydel, renewables and nuclear energy. Kugelman, of the Asia Programme at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, says an overhaul of the energy mix would be about politics – and the obstacles would be daunting. “We need to ask questions about political feasibility: Would Pakistan push forward with increased hydro production, knowing full well the outcry this would elicit from riparian communities and other opponents of large dams? Would Pakistan increase coal production and risk the backlash from environmentalists?” And would Pakistan be prepared to overhaul the structure of subsidies so as to create a level playing field for all?

Because it’s impossible to just stop and reverse the direction of the policy, Pakistan will have to continue to find ways to shore up supply from abroad for decades. That’s why regional integration with its resource-rich neighbours with unexplored oil and gas reserves is a must. Maria Kuusisto has studied Pakistan and travelled the region, and says between Iran and Turkmenistan, Iran is the better bet for Pakistan. Turkmenistan is a former Soviet state and Russia behaves as though Turkmenistan is still in its sphere of influence. Still, integrating with Iran is not without its risks, says Kuusisto. “The security and political situation in Balochistan will create obstacles in the implementation of the project, potentially hindering fulfilment.” Also of concern is the fact that the oil and gas network is hugely underdeveloped in Iran.

Pakistan’s energy future is filled with many uncertainties. As such, a comprehensive strategy for seeing the country out of this mess requires more than hoping and praying that the price of oil stays down. Changing the country’s energy mix by exploiting domestic natural resources more effectively will be key to the country’s energy security, limiting future energy deficits that need to be filled by expensive imports. Estimates of the energy deficit in 2025 could surpass 50% of total energy demand. That means that over 50% of energy needs may need to be imported.

However, the country can’t make the shift by itself. While Pakistan’s legal environment is very international investor-friendly, says Kugelman, outside energy investors are unlikely to bring their capital to Pakistan’s security-challenged landscape. International energy investors also like to see the existence of worthy privatised energy programmes. “Given the recent experience of KESC, investors will not exactly be emboldened on this front either,” he says. Throw in the fact that IPPs are selling to a government who can’t pay, and things won’t look very attractive to foreign eyes.

Volatile politicians screaming on television don’t help either. In July, a PML-Q senator appeared on a current affairs show and proclaimed that if the crisis didn’t improve soon, it would trigger a civil war. The display was probably more of a case of political melodrama and grandstanding. Though Kugelman does, however, see the possibility for more violence if the crisis worsens and exacerbates the various fault lines that already threaten to tear Pakistan apart. “The energy crisis, if it continues, could also conceivably precipitate a series of ominous developments – shuttered factories, rising unemployment, even more water shortage – that could in turn spark prolonged periods of public unrest. Public unrest, however, is far from a prelude to civil war.”

Imtiaz Gul seems to think that we should be worried, though. “Half the country is spending sleepless nights without power,” he says. “This is not a recipe for stability and peace.”

* * *

From where Pakistan stands today, things look bad. Commercial electricity generation grew 48% between 2000 and 2007. However, over the course of fiscal year 2007-08, generation actually fell 2.5% compared to the previous year. That was the first decrease in annual power generation since 1991. And for 2008-09, the trend looks like it is worsening. For the first nine months of the last fiscal year, generation had fallen 18% over the same period a year earlier.

It didn’t have to be this way.

Remembering back to that meeting in Islamabad in March 2005, Shahid Javed Burki recalls the phone call General Musharraf made to Shaukat Aziz. “I don’t know what the prime minister said, but I know he was made aware of the fact that this was a major crisis.” As a result, a lot of the responsibility lies with him. “The PM was a disaster. He did not focus on strategy.” That mismanagement of the crisis was only part of the problem, though. Back then, the PM always gave the impression that things were going well, that the country was on a strong, upward growth trajectory. “He made it sound like we were like the East Asian countries,” says Burki.

There’s little we can do about that now, though. Today a new government must tackle this problem decisively. As Newsline went to press, Federal Minister Raja Pervez Ashraf announced a major meeting for August 5 with the Special Committee on Energy Crisis that aimed to discuss the available plans of action. As politicians argue over the merits and demerits of all the alternatives, Pakistanis can only hope that their focus starts to shift from short-term band-aid solutions to long-term strategic planning. But that involves being honest with all the stakeholders, thinking of the needs of all Pakistanis and having the political will to do what is best for the country, both today and tomorrow.

Pakistan can’t afford a re-run of 2009’s energy saga – ever.

* * *

In March 2011, this article landed Talib Qizilbash a national APNS award for Best Business/Economic Investigative Feature.

The following post/link was a sidebar by the author in the original print version of this article from August 2009: Energy Policy is Not Gender Neutral

Text reprinted with the permission of Newsline Publications (Pvt.) Ltd.